The war was almost over. Germany in March 1945 was cold and crisp, with a pale gray tint over the ruined countryside. It was quiet as Lieutenant Hecker’s jeep drove down the road. Europe was a hulk of shattered cities. The Third Reich was in ruins, its soldiers surrendering by the thousands to the American Army, but still Germany fought on. Lieutenant Hecker rode with his men, Private First Class William L. Piper and James Wardley. They had been together through Northern France, the Hurtgen Forest and the Battle of the Bulge. Now they drove in the enemies heartland. Hecker knew the end of the war was in sight. He knew all they needed to do was stay alive a little longer. What he didn’t know was his jeep was driving toward a buried land mine.

Norbert A. Hecker was a not a soldier by trade. He hadn’t planned on knowing things like range, targeting and trajectory. He was a clerk who compiled reports on factory labor costs and production. When he graduated college he thought he would be behind a desk not leading men into battle. He entered the army in 1942, and was assigned to the 8th Infantry Division’s 28th Field Artillery code named “Gunshot” .

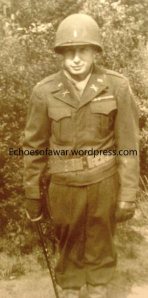

Lieutenant Hecker was a Forward Observer. His mission was to report where artillery strikes landed and find new targets to attack. Forward Observers had a short life span on the front lines. It wasn’t just the enemy that was dangerous, if the observer made a mistake and the coordinates were wrong, or someone else was careless, the called in artillery could land short, right on him.

When the 28th Field Artillery sent out fire, they radioed “Gunshot on the way!”. “Gunshot on the way” was friendly artillery that stopped the advancing waves of enemy armor and infantry, “Gunshot on the way” took out gun emplacements slaughtering pinned down American GI’s. It was that call that could make the winning difference on the battlefield. It was men like Norbert Hecker who brought the gunshot down on the enemy. He knew men were counting on him, that he must complete his mission at all cost. His radio calls could mean dozens or hundreds more men going home alive. It was men like Norbert Hecker who made small towns all over the United States proud of their boys.

In Hecker’s home town of Menasha, Wisconsin, the local paper followed news about its 1,384 residents serving in the World War. The daily paper got the residents atuned to where its boys were fighting and what they were doing. It gave folks the little picture they wanted to see of the big show; the news about the boys they used to see on the streets and in church. The paper spread news of men and women who had been promoted or seen action in big battles. When a local boy got a medal for heroism, the whole town knew. They also heard when a man was wounded, or when a someone’s son would not be coming home.

If Norbert Hecker and his men had been walking, they would have been safe. The mine in their path was a teller mine; a circular, anti-tank device filled with five and a half kilograms of TNT. It had a high pressure fuse and needed a vehicle to set it off.

Hecker’s jeep exploded when it ignited the weapon. James Wardley, by some miracle, was unhurt. Bill Piper, was wounded but alive. They found Hecker covered in blood with his eardrums blown out. But he was breathing. The three men helped each other up. Hecker’s helmet had a huge dent on the top from the exploding debris. Their jeep was destroyed and two of them were wounded. Hecker put his helmet back on, looked at his men, and they continued to the front. The war wasn’t over yet. Until it was finished, Norbert Hecker would see his mission to the end.